It is not often that someone comes along who is a true friend and a good writer. Charlotte was both.

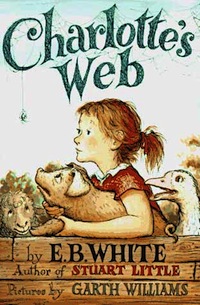

E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web is the story of two unlikely friends: a pig saved from early slaughter only to find himself being fattened up for Christmas, and a rather remarkable spider with a gift for spinning words. Also, a very mean rat, a wise old sheep, a goose very focused on her eggs, a determined girl, a bit where a lot of people fall down in the mud, and a Ferris wheel. Warm, funny, wonderful—at least, that’s how I remembered it.

And then someone on Twitter had to spoil all of these happy childhood memories in one tweet.

Said someone was the gifted and always amusing Tansy Rayner Roberts, who noted a few gender issues with the book, summing up Charlotte’s Web with this zinger:

Seriously, it’s about how the female spider does all the work, the male pig gets all the glory and then SHE DIES HAPPILY AT THE END.

This being Twitter, you will not be surprised to learn that this tweet generated a lot of reactions before reaching a final, rather comforting conclusion that everyone should just eat some bacon. In revenge.

Also, it reminded me that I still hadn’t gotten around to blogging about E.B. White yet. So here we are.

Before we dive into this tweet, I do want to say, in my own defense, that my childhood memories were not entirely wrong. Charlotte’s Web is about a pig and a spider, although initially, that’s hard to see, since the first few chapters focus on Fern, an eight year old girl extremely upset to find that the runt of the latest pig litter is going to be killed. After she argues that this is the most terrible injustice she’s ever heard of, her father allows her to save the tiny pig, whom she names Wilbur. Fern keeps the pig as a pet for a few weeks—the illustrations of Wilbur in a doll pram are particularly adorable—bottle feeding the baby pig and basically saving his life. Girl save number one!

Unfortunately, the rescue doesn’t last: Fern’s father, John Arable, insists on selling Wilbur when the pig is only five weeks old. Fortunately, the pig is sold to Fern’s uncle, Homer Zuckerman, which means that Fern can go down the road and visit the pig whenever she likes. Unfortunately, Mr. Zuckerman, a very practical farmer, has only bought the pig in order to fatten him up and butcher him in the winter.

Well, unfortunately from Wilbur’s point of view. The Twitter point of view is apparently, yay, more bacon! But Twitter is perhaps a bit bitter.

Anyway. Wilbur, initially ignorant about this—he is a very naïve little pig, perhaps not that surprising given that he’s only been in two places in his very short life, and spent much of that life dressed as a doll—is at first mostly beset by boredom. After five weeks of getting played with and taken places, he is now trapped in a small pigpen, with only occasional visits from Fern. He desperately wants a friend.

And along swings down Charlotte, ready to be his friend—and save him.

But although this friendship plays a central role for the rest of the book, as it turns out, this book really isn’t about friendship at all, but rather about growing up, and accepting that part of life is death.

On a first glance, this might not seem quite that obvious, given that the majority of the plot is about keeping Wilbur alive—something that is ultimately successful. But to reach that point, Wilbur has to accept that his friend is the sort who regularly kills other creatures and sucks out their blood—a poignant scene immediately followed by a slapstick scene where Wilbur tries to prove that he, too, can spin a web.

And he has to accept that yes, he actually can die.

That’s the scene that convinces Charlotte to save him—partly because Wilbur is her friend, partly because she thinks that what the farmers are doing—fattening up Wilbur with the best of the scraps while plotting is death—is just wrong (this coming from a blood sucking spider, to drive the point home)—and mostly, it seems, to shut Wilbur up. (Yes, this is in the text.)

But what’s striking about this, and other scenes, is just how passive Wilbur is up until Charlotte’s death. Everything he does is in reaction to something else, or at someone else’s urging—even the scene where he runs away is prompted by the goose (and he’s pretty easily captured again with the promise of food). His reaction to hearing about his forthcoming death is to wail and wail and wail until Charlotte tells him to shut up. He allows himself to be moved from place to place, following instructions and advice. And he contributes absolutely nothing to his own rescue plan—that is entirely the work of the old sheep, Templeton the Rat, and of course Charlotte.

It’s not until Charlotte’s death that Wilbur finally does something on his own—saving Charlotte’s daughters, with the help of Templeton—now that Wilbur has finally learned how to bribe the rat.

Some of this goes back to an observation made over and over again in the text: Wilbur is a very young, very innocent pig who knows pretty much nothing about how the world works—even the enclosed world of the two farms he lives on. Some of it is also because Wilbur really is fairly helpless—he’s trapped in a small pen, he has very few friends, the only human he can communicate with is an eight year old girl who pretty much loses complete interest in him once she’s had the chance to jump on a Ferris wheel with a boy, and—unlike the fictional pig created by White’s colleague Walter Brooks—he doesn’t have any other resources.

But some of it also goes back to Tansy’s observation: this is a story of a woman spider saving a male pig. And for a pig to be rescued by a spider, that pig has to be very helpless. Can we stretch that to if a guy needs to be rescued by a woman, he has to be very helpless? Er….well. Let’s stick to pigs and spiders.

But it goes a bit deeper than this. Again and again in this book, the women are the ones doing the rescuing and saving: Fern, her mother (who makes the fateful suggestion to send Wilbur to a friendly farm), the goose (who schools Wilbur on certain realities, and is technically the person who saves Charlotte’s life, allowing Charlotte to save Wilbur), the old sheep (who is the one to persuade Templeton to help out at the fair) and, of course, Charlotte. On a small note, the one person to appreciate this is also a woman:

[Mr. Zuckerman] “…A miracle has happened and a sign has occurred here on earth, right on our farm, and we have no ordinary pig.”

“Well,” said Mrs. Zuckerman, “it seems to me that you’re a little off. It seems to me we have no ordinary spider.”

Her idea is rejected. The men insist that Charlotte is just an ordinary grey spider. Though,I will say, to their credit, they’re less freaked out than I would be if I saw actual words in a spider web.

So yes, I think that something is going on here.

Meanwhile, I’d forgotten just how much of the book is about the other animals on the farm: the geese, their little goslings, the sheep and the cows. Perhaps they are less memorable because they are not under imminent threat death, or perhaps because they are simply nicer and blander than Templeton the Rat. Well. Everybody is nicer and blander than Templeton the Rat. I’d also forgotten that there is a minor character with the unfortunate name of Henry Fussy.

One other small thing that nags at me: why did not one, but two staff members at The New Yorker end up writing children’s books focused on fictional talking pigs beset by terrible boredom who end up having lengthy conversations with fictional spiders? The original Freddy the Pig book even used a similar narrative structure where the animals could talk to each other and understand human speech, but couldn’t speak directly to humans, even if this approach was later abandoned.

It’s impossible for me to say just how much influence the two had over each other—they knew each other, certainly, and worked together, and I think it’s possible that White’s decision to write books about talking animals was at least in part inspired by Brooks’ success. Also, of course, the success of Winnie the Pooh and several other talking animal books—including, possibly, Oz. And the two pigs aren’t that similar: where Brooks used his fictional farm animals for comedy and, later, fierce political satire, White uses Wilbur to develop a mediation on death, and the need to accept it. But that still leaves me wanting to know just what was going on at the New Yorker during the 1930s.

Mari Ness still likes bacon, even after reading this book, but she draws the line at eating spiders. She lives in central Florida.

I have to admit that I’ve never read the book, although I loved the animated film as a kid, even though it made me cry.

I’d like to think that E.B. White, if he were to read about this discussion of the book, would be glad to see that someone finally got it. For in truth, it is the spider that is special, not the pig.

— Michael A. Burstein

Copy editing:

“But to reach that point, Oliver has to accept that his friend is the sort who regularly kills other creatures and sucks out their blood”

Who’s Oliver?

And I thought the girl’s name was Fern, but you call her Fran for half the post.

If a man saves a woman, it’s problematic because the woman lacks agency and fulfills damsel in distress tropes. If a woman saves a man, it’s unfair. When all you have is a hammer…

Wait, so I’m confused – if the book is about all these women doing the right things, saving people (pigs), then isn’t the message pro-women? Sure the men get the credit (mostly from other naive men — the farmers), but maybe that’s just a cynical, un-ironic statement about the way of things at the time? I didn’t get the impression that we’re supposed to be happy Charlotte dies at the end.

Besides, I can imagine the hand wringing were the gender roles reversed:

Helpless, passive Wilburina needs a strong intelligent male spider Charles to save her from a horrific death.

Yea, I’m sure no one would have anything to say about that.

Are you at all familiar with Ruth Chew? I was reminded today of a book I loved to pieces as a child, called What the Witch Left. Apparently, she wrote a whole bunch of children’s books about witches!

This was the book that made me very uncomfortable with the general concept of animal fables.

If the animals are sentient and sufficiently intelligent to talk to each other — even cross-species — then it’s clearly unethical to be eating them, and probably unethical to be keeping them penned up in a farm. And the humans, of course, are totally unaware of this.

That tweet has about as much bearing on the story as describing Wizard of Oz as “Two women fight to the death over a pair of shoes.” It seems to me that Charlotte is the very definition of a mother figure here, rescuing Wilbur, yes, but also raising him, teaching him, and ultimately leaving him a better person. Of course, there is a sub-branch of feminism that views “motherhood” as a dirty word.

So yes, “Woman saves man and man takes credit” is one view but so is, “A mother saves her adopted son from a bunch of idiot males,” or “Three strong-willed women work together to save a boy who doesn’t deserve it, but who grows up into a better person because of it.”

Actually, typing that sentence out, makes me realize that we can’t really talk about this story without including the Christian concept of undeserved grace. Is Charlotte a Christ figure?

First of all, who in God’s green earth are Oliver and Fran????

Second, isn’t the old sheep male?

I’m a bit attached to this book in part because it was the first chapter book I ever read on my own. It was my favorite book for a long time. And I don’t EVER remember feeling like the message for me as a girl/woman was to sacrifice everything and die happily becuase I’m a woman. I can see how a similar plot, handled a different way, could have that type of implication, if there was a lot of focus on the genders. But there isn’t. They are characters who happen to be male/female, but that’s not really important (well, except for Charlotte needing to be female because she has to make the egg sac…I suppose you could ask, why is that in there? And I do wonder – was it so it could hammer home the theme of growing up, with Wilbur taking the role of elder in the end? Is there scientific credence to the idea that female spiders die after laying their egg sacs, so he introduced that as a plot-convenient way to have Charlotte die, to hammer home the theme of loss/growing up? Or maybe he made the spider female from the start, and then those plot points came out of that – I actually don’t know the writing process of the book, so I’m just throwing it out there)…I don’t think that the gender of the characters was selected as a way to provide a message about the gender or what people of that gender should be.

Anyway. I’ve actually enjoyed ruminating (oh man, not intentionally making farm puns!) on this…but ultimately I remember as a young girl I wanted to be like Charlote – smart, witty, take-charge, not one to lose her head, etc. I never thought of her death as a necessary part of that (and indeed, the death really has nothing to do with her saving of Wilbur – it’s not through saving Wilbur that she dies, it’s just a part of her natural life span/cycle).

@6,

Disney’s A Little Mermaid is far worse, Ariel falls in love with and marries a man who kills and eats her sentient fish-friends, and she does totally know it.

@7 Nope, because she get’s preggers and has baby spiders, so she clearly must be taking part in some very un Christlike actions off screen with a hunky male spider (who I assume then goes on to bite Peter Parker)

@8, some spiders (although not all) do die after laying their eggs, which overwinter and hatch in the spring.

Although, speaking of egg-laying, this implies that at some point Charlotte mated with a male spider, and probably ate him as soon as the deed was done. I don’t even want to try and fit that into the neofeminist narrative!

@9 Also, I remember in the Doctor Dolittle books that he has no problem with eating meat. And in the Narnia books, nobody human (or humanoid) seems to have any problems with eating non-talking animals.

@12, didn’t Narnia, like the Gregory Maguire Oz books, differentiate between animals and Animals?

Sorry about the names, folks–everything should be fixed, now. Also, please enjoy the mellow musical stylings of Paul Lynde and Agnes Moorehead from the 1973 movie version by way of apology :)

http://youtu.be/nAUEOlSpVN4

I loved this movie as a kid and still do but didn’t read the book until I took a children’s literature class in college. Of the 10-12 books we read a character died in all the books but one. Charlotte’s isn’t sacraficing herself for Wilber or because of him. She dies because it’s the life span of a spider. Though what she does saves Wilber and only he and the animals know it and not the people. It doesn’t matter if they do or not. Wilber will tell Charlotte’s daughters of her gift to him.

:: head in hands ::

Sorry about the names, guys. I blame two factors:

1. Not the best excuse, but I do deal with general chronic fatigue, which causes me to make a number of errors/memory mistakes. Because of this, I generally try to write these posts in advance so I can catch these mistakes, but this time I didn’t catch them.

2. I don’t love this book anymore. But I don’t hate it, either. And the worst posts for me to write, and the ones where I do tend to make mistakes, are the ones where I don’t care passionately about the books either way.

I blogged about these last two books (and will be blogging about The Trumpet of the Swan) because they are iconic, and I’m trying to cover iconic children’s books along with lesser known, more forgotten books.

So with that out of the way, I’m going to bow out of this conversation, and leave you guys to it.

Mary Daly pointed out the gender thing clear back in ’79 or thereabouts. Me, I kind of enjoyed the book when I first read it, but I think even then I may have wondered “Is a con job, committing false advertising, okay if it’s to save someone’s life?” I guess I figured that it was, sometimes anyway. And I was never fully comfortable with [apparently] sapient beings, talking and reasoning and so on, still living as captive animals, not outwitting their captors and finding homes or kingdoms of their own. Talking animals should be more like Winnie the Pooh or the cast of the Wind in the Willows–their means of support might be shadowy, but they were no one ‘s slaves and no one’s dinne. (I’m still hunting, though, for a book I heard of that tells the latter story from the weasels’ point of view.)

Even so, I once walked into a branch library at the exact moment that the storytime lady came to the last 2 sentences of Charlotte’s Web–and I must admit my eyes stung.

One other small thing that nags at me: why did not one, but two staff members at The New Yorker end up writing children’s books focused on fictional talking pigs beset by terrible boredom who end up having lengthy conversations with fictional spiders? The original Freddy the Pig book even used a similar narrative structure where the animals could talk to each other and understand human speech, but couldn’t speak directly to humans, even if this approach was later abandoned.

Perhaps a statement about the relationship between writers and editors at The New Yorker. Who the blood sucking spider is in that situation is up to you. Hehe.

Seriously though, this is a good article, Mari. But the tweet that inspired it, well, it reminds me of that line from the film Contagion: “Blogging isn’t writing. It’s graffiti with punctuation.”

Honestly, I called that book as bullshit when I was 7 right at the start when Fern saves the pig then goes and has bacon for breakfast before she heads to school.

What I remember disliking about it was the way Fern falls out of the story and apparently turns into someone else entirely.

Interesting take. I can see how adults may look at it that way and read into the book a meaning seeing as they do through their adult lens. The tweet may have been provocative (it got you to write a whole post about it), but does the idea have substance? Especially when you put this book into context, specifically that it was written for children, not adults, and follows the classic arc of a coming of age story. As you rightly point out, the central theme is the acceptance of death as part of life. This is a lesson that all must learn on the way to becoming an adult and is a common theme in juvenile literature. Wilbur is, as you said, very young and inexperienced. He is a juvenile. And Charlotte is older and more experienced. She is an adult. And like so many coming of age stories, the protagonist is passive – others making decisions for him/her, etc. – until the catalyst to change, i.e. to growing up. Here it’s Charlotte’s death. Looked at in the context of a children’s book, it follows the classic arc of many coming of age stories (especially stories from the 20th century). So while it can be read with the feminist bent of the tweet you mentioned, I’m not sure it’s as much about gender as it is about coming of age.

Your paragraph above about how passive Wilbur is throughout until the death of Charlotte reminded me of my own tween daughter and perhaps other parents of tweens/teens may relate. So through my lens, I’m seeing the mother/child or mentor/mentee relationship more than I’m seeing it as strictly a gender issue. I think you could make Wilbur a female character and you’d have the same story, IMO.

@Angiportus:

I don’t know if you will see this, but you wrote:

“I’m still hunting, though, for a book I heard of that tells the latter story from the weasels’ point of view.”

That would be Jan Needle’s “Wild Wood”.

Regards, Faheem

Your post inspired a homework assignment of mine!

Here it is:

In a Twitter post dated September 25, 2014, Tansy Rayner Roberts said of Charlotte’s Web, “Seriously, it’s about how the female spider does all the work, the male pig gets all the glory and then SHE DIES HAPPILY AT THE END.” I think she’s missing the point that while Charlotte had no choice about her instincts to eat bugs and produce an egg-sac, for example, she chooses to parent Wilbur with all the noble non-glory that comes with parenting.

When Wilbur meets Charlotte, she promptly kills a fly, describing in detail how she does so and that she drinks its blood. She comments, “I am not entirely happy about my diet of bugs and flies, but it’s the way I’m made” (p. 39). When Wilbur balks further, she defends her instinct, pointing out that no one serves her food, and that her diet serves an ecological function. It reminded me, perhaps strangely, of how women have been criticized about their biological functions (like menses, childbirth, breastfeeding, and menopause) although they are a natural function and serve a biological purpose crucial to the continuance of human life.

Wilbur himself is a pioneer for liking her not only for beauty, but her brain. He says, “‘…she is pretty and, of course, clever” (p. 41).

Charlotte’s choice comes at the end of Chapter 7, when Wilbur finds out from the sheep that he is slated for the chopping block. Charlotte makes a decision that she will save Wilbur and commits to him on page 51:

‘You shall not die,’ said Charlotte, briskly.

…cried Wilbur, ‘Who’s going to save me?’

‘I am,’ said Charlotte.

From that moment on, she begins to parent him, telling him to stop crying. The next time we see them together, she is indulging Wilbur in his fantasy that he can spin a web, much like a mother lets her daughter play at being like mommy. She cheers him when he is unsuccessful and defends him when he’s picked on by the lamb. “Let Wilbur alone!” she says (p. 61). In the same chapter, Charlotte chastens him about hurrying, worrying, chewing his food thoroughly and getting enough rest (pp. 64-65). If ever there was an exchange moms can relate to, it is this one on page 65, “No more talking! Close your eyes and go to sleep!” which is promptly followed by three more “Good night” exchanges between Wilbur and her.

Another time she chose to parent Wilbur was when she modified her plans to lay her eggs in the barn and chose to go to the fair. Wilbur did not ask her to, nor did any animal pressure her. She chose (p. 122). The book is peppered with Charlotte smiling at Wilbur, telling him good-night stories, and singing to him. Clearly she loves motherhood. She performed her service willingly.

On their last day together, Charlotte says to Wilbur, “Your success in the ring this morning was, to a small degree,my success” (p. 163). She underscores her fondness for Wilbur, the preciousness of friendship, and the nobility of her choice:

‘You have been my friend,’ replied Charlotte. ‘That in itself is a tremendous thing. I wove my webs for you because I liked you…By helping you, perhaps I was trying to life up my life a trifle’…’Well,’ said Wilbur…I would gladly give my life for you.’

Their is a reciprocity to their affection and willingness to care for each other, now that Wilbur is grown. Charlotte may be a slave to her instincts and form, but she chooses to be a mother figure, and understands the sacrifices and benefits. In ones mind, the genders could be changed and nothing about the story changes.

White himself seemed to appreciate woman, for it is Fern and Charlotte who save Wilbur, Mrs. Zuckerman who appreciates that it is Charlotte who is the remarkable creature, and all of the female animals in the barn who nurture and teach. The men, with the exception of the doctor, are brutes (Templeton and Avery), bumblers (Lurvy), and simple-minded (Mr. Zuckerman and Mr. Arable).

Heh. To me, the star of the book was ever and always Templeton, who gave me a longtime love of rats. Villain (by inclination, allegedly), glutton, snarky, eloquent, helpful…yeah.

OK, Charlotte was also cool.

There’s a good reference to Charlotte’s Web in the cartoon Non-Adventures of Wonderella. Made me laugh.

Its all ferns imagination with the talking animals. And yes, it is fern who came up with writing a word in a web and she did it. You can kill a spider and make the webbing come out. That’s the only cynical part about this book. Fern is Charlotte. But she had to kill a spider every time a word was written in a web

Feel like I lost some brain cells.

Obviously it was a mother son relationship, that transcends a women doing all the work for a man, or for a boy. Twitter eh

As always, we ask that you approach discussion on the site in a civil, constructive manner. Rude, insulting, aggressive, and dismissive comments will remain unpublished–you can find our full commenting guidelines here.

Always found this to be a very disturbing film. What is it basically preaching to children anyway? Life sucks and then, you’re gonna die. That woman’s voice- I guess the spider, so flat, unemotional and creepy. Truly a grim and horrible story that no one should have to sit and listen to

I found it very progressive, actually, that the kick ass heroine saves the hapless male guy. I fail to see the problem. Would the reverse have pleased you? Strange. Also, by the way, Charlotte dies after laying eggs, because well, that is what many spiders do. That also ties in with the theme of love, loss and growing up prevalent in the book. And when all is said and done, these are animals. For them, the procreation thing is not as much of a feminist issue, to my limited knowledge. And I felt like the subtext was that Charlotte is the real hero ( I mean, she is the one in the title). You really can’t complain about the gender politics here.

I don’t worry too much about the gender of the characters. I am more concerned about the romanticization of sacrifice to the point of suicide. Teen suicide is very much this dramatic romantic gesture they are inundated with. Romeo and Juliet, Lion King, Charlotte’s Web, etc. Die for the love of another! It’s the most beautiful thing imaginable!

Maybe we could stop throwing that idea at kids

Whoa, whoa, hold on — the farmer’s name is Arable? How did I grow up as a fan of this book and movie without ever noticing that pun, or having my pun-loving older family members point it out to me?